DRS – A variable deposit scheme is the only logical and fair approach

New poll highlights consumers preference for variable rate

In May, the Scottish Parliament voted to approve the introduction of its drinks container deposit return scheme (DRS). This will become law as of the 1st July 2022.

It’s always disappointing when governments brush aside sound and well-researched arguments from those most likely to be affected by proposed legislation; and doubly so when the same reasoned arguments, backed by research, have been made by professional organisations and trade bodies.

It’s not that the sector is against a DRS in principle, although of course it could be argued that packaging does not litter itself, in which case why should the supply chain be required to pay to deal with a problem that is actually a criminal offence under UK law? No, that argument was lost some time ago so now the supply chain is now left having to contemplate an extremely expensive alternative, one that many believe will do little to improve the recycling rate of the best performers.

For example, not only do aluminium drinks cans already have a recycling rate above 75 per cent, but they are also produced by a sector that is working hard to increase this still further through excellent, industry-led, consumer-facing campaigns such as Alupro’s Every Can Counts and MetalMatters.

In fact, the drinks can industry largely believes that, left to its own devices, it would be able to match the Scottish DRS targets via such well-established and highly successful schemes, but in a far more cost-effective and consumer-friendly manner.

But, the legislation is here to stay and it does have some good points, the gradual increase in the required recycling rate for one, and the fact that by year three, each packaging material in scope must hit its own target rather than relying on other materials to lift the overall average.

The big problem centres on the flat 20p per container deposit which many believe will have serious implications for the sale of single-serve and multi-packs.

And how can it not?

Imposing a flat deposit rate immediately creates two market inequalities: firstly, the deposit cost per litre of the product will vary vastly depending on the pack size; and secondly multipacks and single-serve containers will be penalised over the far larger multi-serve plastic bottles.

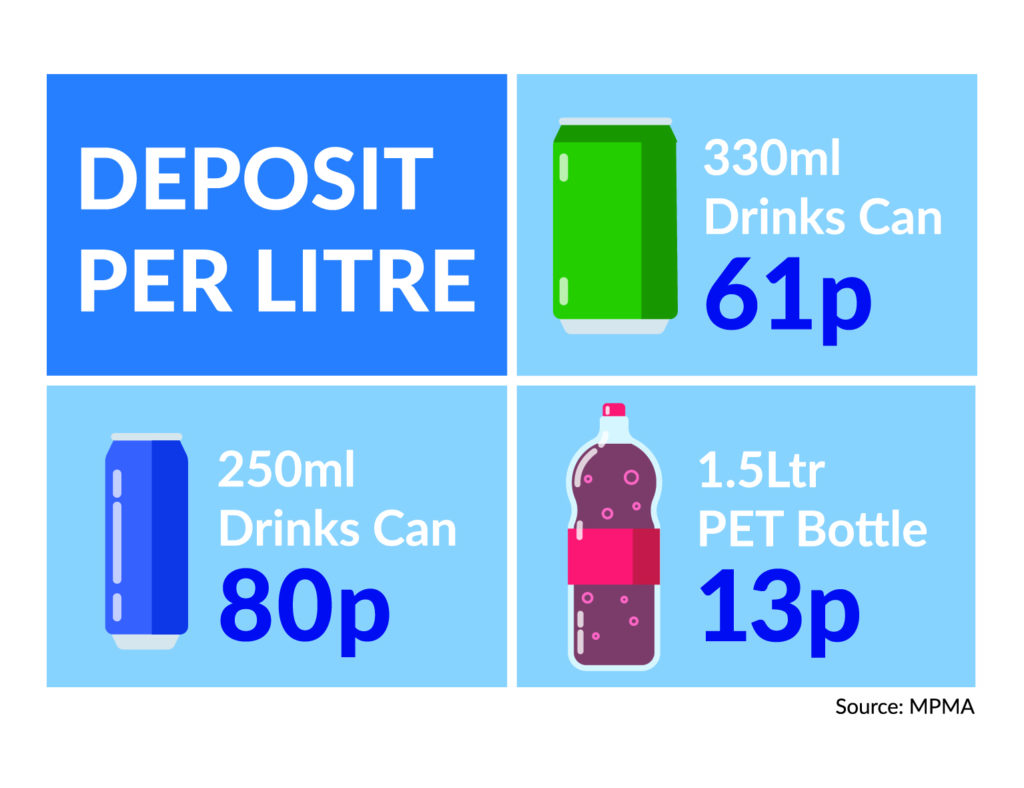

For instance, if we look at the deposit cost per litre for a range of common drinks container sizes:

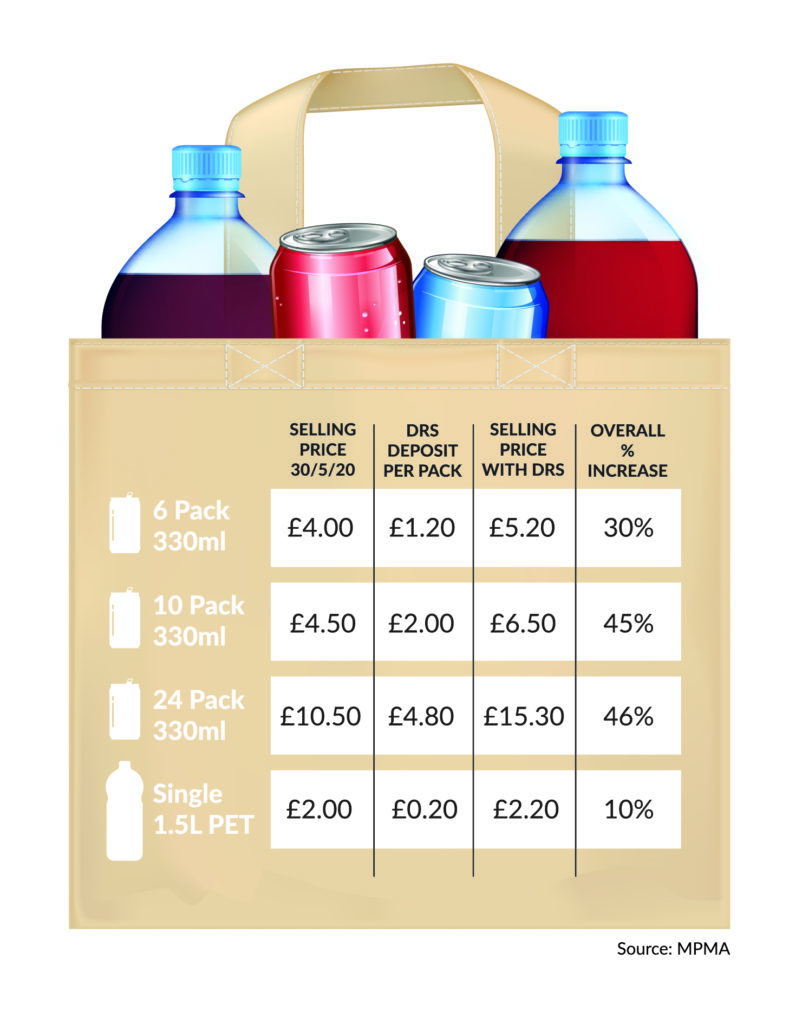

If we then look at the case of multipacks of single-serve drinks vs. large plastic bottles (current prices are for a leading fizzy drink sold at a Scottish retailer):

As you can see, in both cases the single-serve and multipack offerings will be significantly disadvantaged over the large multi-serve plastic bottle.

Interestingly a poll by environmental group, Nature 2030, suggests that while 84 per cent of people agree that all drinks containers should be included in the DRS, almost four-in-five suggested the scheme should have a variable deposit. This data contrasts greatly with previous government consultation findings, which conversely suggested that 57% of the public instead favoured a flat fee.

It has been suggested by those defending the flat deposit approach in Scotland that we are worrying about nothing as the consumer will get their deposit back when they return the empty cans. I have to say, to me, this feels rather like Marie Antoinette’s alleged quote “let them eat cake”, since if you are shopping on a budget, like so many are, it doesn’t matter what you will get back next week, it’s all about what you have now, and how to make this week’s housekeeping go as far as possible.

The evidence from us and other organisations is irrefutable, a flat deposit per container will cause market distortion and will push families on low and modest incomes towards the large format plastic bottles as it will be their only means of minimising the increase caused by the deposit scheme. It’s, therefore, no surprise to discover that the most successful DRS schemes in Europe all have variable deposits per litre.

The other issue, of course, is that to be able to maximise the self-financing of a DRS scheme you need as many aluminium cans as possible as it’s the aluminium that provides the most value. Thus, by disproportionately increasing the selling price of aluminium cans over large-format plastic bottles, not only does the scheme adversely impact the consumer, it also adversely impacts itself and as a result, will require more external funding to operate.

Surely, the only logical and fair approach is to have a variable deposit scheme based on the volume of the product being sold. The alternative causes too many problems for too many people.